Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Fairest of Them All: Cos d’Estournel 1928 – 2015

BY NEAL MARTIN | OCTOBER 2, 2018

Question dear reader... What are the three best vistas in Bordeaux? Runners-up are surely the Doric pillars at Château Margaux in the morning light and the two Pichons, Baron and Comtesse, wistfully gazing at each other on the horizon as the road sweeps down from Léoville Las-Cases.

The winner is…?

The winner; no filter by the way

Unquestionably the startling sight as Cos d’Estournel blazes into view heading up from Lafite-Rothschild, its incongruous extravagant Oriental facade decorated with towering pagodas, pachyderm-themed statuettes and Raj-influenced flourishes, set aflame in golden sandstone. It stuns any first-time visitor because it is so unexpected. Bordeaux châteaux adhere to a strict dress code – suit and tie. Granted there are one or two attired in fairy-tale garb. I could imagine Rapunzel leaning out the window of say, Palmer or Pichon Baron waiting for her prince to arrive on his steed and making do with Thomas Duroux or Christian Seely instead (no offense guys). But mostly Bordeaux is practicality over pulchritude. You have to journey to the Loire for idyllic châteaux with moats carpeted with water lilies, extravagant witches’ hat spires and perhaps the odd drawbridge/portcullis combo. Cos d’Estournel is Bordeaux’s notable exception, a château that flagrantly ignores that dress code. I recently sat and observed tourists pulling over to take photographs, posing in front of its triumphal arch with its ancient “Zanzibar door” behind. Nobody notices the man sitting stationary under a tree upon a bench and yet without him this château, Cos d’Estournel would not exist.

But he is there.

You just need to look.

If the design of Cos d’Estournel is unorthodox, then the wine itself adheres more to what we expect. It errs towards a comparatively sumptuous and occasionally flamboyant style that stems from its propitious planting’s of old Merlot, yet there is always the countervailing density and earthiness one seeks from classic Saint-Estèphe, not to mention longevity, as we shall see. I have been visiting the property for two decades however, throughout my professional career, older vintages have been few and far between. On the rare occasions they do appear, such as the 1955, 1964 and 1966, I have been deeply impressed, the latter a revelation when I was starting out in my career. After many months discussing a vertical tasting with the team at Cos d’Estournel, I was finally able to spare an afternoon inspecting the vineyard and winery and of course, taste through vintages spanning many decades. Fans of Cos d’Estournel should treasure this piece. There are very few remaining ancient bottles residing at the property and you rarely witness so many ex-château bottles together in one sitting. Some of them had fallen by the wayside. Others were spellbinding.

Firstly, let’s have a look at the history of Cos d’Estournel to find out how it became that most dandiest of the Grand Cru Classés.

History

The d’Estournel family hailed from Quercy in the Lot département. Louis Gaspard d’Estournel was born on 3 January 1762 and at the age of twenty-nine, inherited the “maison noble de Pommies et de Caux”, “Pommies” referring to what is presently Château Pomys and “Caux” the name of the hill to the north of Lafite-Rothschild whose spelling mutated into “Cos”. Not satisfied with his inheritance, Louis Gaspard augmented his holdings with further purchases of land around Bordeaux. According to Clive Coates MW, it was during a summer afternoon in 1811 that Gaspard stood in Lafite, gazing northwards towards his parcel of land and noticed similarities with their respective aspects and soils.

It was his eureka moment.

Gaspard realized that it was possible to produce a wine of similar standing to Lafite. At that time much of Saint-Estèphe was scrubland, awaiting vines. He planted around 12 hectares, but in the same year he suffered foreclosure for an outstanding sum of just 250,000 Francs. Fortunately, thanks to some clever small print and/or clauses inserted into the contract of sale, he was able to remain proprietor of Cos and in a twist of fate, persuaded the beneficiary of his foreclosure to sell the shares back to him in 1821.

Surely relieved to have kept his hands on his beloved estate, Gaspard expanded the vineyard to 57 hectares between 1821 and 1847 via the acquisition of 80 parcels. This included the neighboring Cos-Labory whose choicest plots were incorporated into Cos d’Estournel, (which might explain why Cos-Labory has remained in its shadow). From the 1830s Louis Gaspard began to construct his fancy winery. Influenced by his travels to the Orient and especially to India, where he traded and bred Arabian stallions, he integrated an Indian aesthetic, mixed with Chinese pagodas and towers, all in refulgent sandstone. Looking out onto the road he constructed a triumphal archway inscribed with the motto “Semper Fidelis” or “Always Faithful”, the motto of the US Marine Corps. Directly behind, an ornately decorated wooden door imported from the Palace of Zanzibar in the early 1800s. (Incidentally, when I drove past in early August this year, the so-called “Zanzibar Door” was covered in black tarpaulin following an arson attack on 25 July this year. It begs the question – why?)

Inevitably Louis Gaspard became known as “The Maharaja of Saint-Estèphe”. One might expect he designed a flamboyant château to inhabit and yet Gaspard remained in his perfectly decent abode at Château Pomys. Indeed, there has never been any residential aspect to Cos d’Estournel, leading one to conclude that it was Gaspard’s adoration for his vineyard manifested in the architectural finery. This expansion and construction ran in tandem with a growing reputation for the quality of the wine. Unsurprisingly Cos d’Estournel was classified a Second Growth in 1855. Sadly, Gaspard was not there to enjoy just reward for his foresight and efforts. He was forced to sell the estate in 1852 and died a year later. If you look towards the Lafite-side of the château, under a tree you will see a statue of Louis Gaspard commemorating his achievement, the man I mentioned in my preamble. Say hello next time you are there taking photos.

In 1852 Cos d’Estournel sold for the princely sum of 1,150,000 Francs, including Cos Labory and Pomys. The purchaser was Charles Cecil Martyn, a Parisian-based Londoner financier, though he remained an absentee landlord. Martyn sold off Cos-Labory in 1860, then other estates in 1869. However, Martyn assiduously appointed Jérôme Chiapella, the proprietor of La Mission Haut-Brion and négoçiant, to take care of Cos d’Estournel. Can you see the irony? Chiapella’s own estate in Graves was unfairly ignored by the 1855 classification and yet he agreed to run a Second Growth up in Saint-Estèphe. I wonder if Chiapella coveted ambitions to buy Cos d’Estournel himself to rectify that injustice. The 1860s saw further improvements, ensuring that it vied with the likes of Léoville, with prices to match. Workers were generally well looked after with free medical care and housing facilities, much like Montrose at the time. Whether or not Chiapella had motives to buy Cos d’Estournel, it was not to be. In 1869, ownership passed to a gentleman by the name of “Errazu”, a bon viveur whose tenure lasted two decades. Wines from this period are renowned, purportedly equal to coeval First Growths. It was then sold to the Holstein brothers. Subsequently in 1894, Cos d’Estournel passed into the hands of Louis Charmolüe, the owner of Montrose that married Holstein’s daughter and heiress. It is for this reason that many of the ancient bottles of Cos d’Estournel reside at Montrose, much to the current owner’s chagrin.

In 1917 Fernand Ginestet acquired the estate as well as Château de Marbuzet. His daughter Arlette inherited the property and married into the Prats family. She had three children, Jean-Marie, Yves and Bruno. It was the charismatic Bruno Prats who undertook the management of Cos d’Estournel in 1971 and became synonymous with the estate, an ambassador par excellence. In 1998, family inheritance issues saw the estate sold to the Tailan group and Argentinean investors, though their tenure was short-lived. In 2000, Cos d’Estournel was sold to Geneva-based entrepreneur, Michel Reybier, a quiet and private businessman who had made his fortune in the food industry, and who is nearly always present whenever I visit. Reybier requested Jean-Guillaume Prats to take over from his father to maintain continuity, slipping into a directorial and ambassadorial role as good as his father.

Technical Director Dominique Arangoits out in the vines

It was around this time that I made my own first visits. I remember one grand dinner in 1998 when large formats, all decades too young, were served. What I recall the most however, is a small commotion as Bernard Ginestet entered the room. Jean-Guillaume Prats was assisted by technical director Dominique Arangoits from 2004, a quietly spoken and erudite winemaker who probably deserves more credit for overseeing some spectacular recent vintages. In a twist of fate, Jean-Guillaume Prats can now be found helping Saskia de Rothschild run the First Growth where Louis Gaspard experienced his eureka moment. Aymeric de Gironde succeeded him in 2012 and he himself departed in 2017 to oversee the rebooted Troplong-Mondot. Currently Michel Reybier’s team runs the estate. In March 2017 he acquired Château Pomys, reuniting Louis-Gaspard’s original holdings that had been sold off in 1869. Earlier this year, it was announced that they would launch a luxury “COS100” cuvée from a plot of century-old Merlot planted by women in 1915, when men were fighting in the trenches. Released only in large formats and uniquely for the 2015 vintage, the proceeds go to charity.

The Vineyard

The 100-hectare estate comprises 70 hectares of vine that surround the property on top of the hill it cohabits with Cos-Labory. Cabernet Sauvignon is planted on the higher reaches of the vineyards and Merlot on the lower. A map dating from 1947 shows at that time, just 35 to 40 hectares were under vine with large tracts of pasture. The vineyard comprises a 16-metre elevation, although that only takes it up to a “lofty” 19 metres in height, yet that is sufficient to accommodate a variety of favorable exposures and orientations. Generally, there is a high gravel content and less clay than other Saint-Estèphe vineyards, which means its soils are particularly free draining. Like many Bordeaux estates, the team has undertaken soil analysis in recent years. In 2000, one hundred pits were excavated around the vineyard to examine soils types. Four years later, advances in technology allowed them to conduct a resistivity analysis to paint a more accurate picture. They discovered 19 different soil-types that form the template to treat the vineyard as individual blocks, each vinified in their own dedicated vat. The first block that I inspected during my visit was a 14-hectare parcel on the eastern slope, which is exposed to the wind and the afternoon shade and is suitable for Merlot, whereas on the south-facing slope towards Lafite-Rothschild, there is a majority of Cabernet Sauvignon planted in 1961 and 1962 after the frosts that affected Bordeaux in the former year.

Looking up towards the château hopefully gives some kind of perspective; this was taken from the merlot vines lower down the slope

“We use mainly 420 rootstock,” Arangoits explains as we examined the vines. “I prefer this because it tends to ripen later, but we also have 101-14 and 3309. We stopped using pesticides two years ago – in 2015 – and now we use sexual confusion techniques.”

The vineyard currently consists of 58% Cabernet Sauvignon, 38% Merlot, 2% Petit Verdot and 2% Cabernet Franc. I have included blends for respective vintages in my tasting notes where they were recorded. It seems like a “seasoning” of Cabernet Franc and Petit Verdot only entered the Grand Vin around 2000. As I briefly mentioned, it is the Merlot, especially its oldest vines that impart the more opulent style of Saint-Estèphe. The average vine age is 35 years planted at between 8,000 and 10,000 vines per hectare.

The Winery

I have already described the château’s distinctive Oriental design. Pathways are flanked by tall palm trees that enhance the tropical look and elephant shaped bushes that, to Jean-Guillaume Prat’s dismay, refused to grow, leaving just a bare wire cage and a recalcitrant shrub at its base. I vividly recall him escorting me around the new winery just after its completion. It was quite an eye-opener. Its modernism in the form of smoked glass pillars and tenebrous lighting were in stark contrast to the almost Luddite cranks and pulleys. They were clearly eschewing automation, which was the watchword for two decade’s progress in Bordeaux. Cos d’Estournel seemed to be winding back the clock, embracing mechanics and physically maneuvering entire lots of wine as smoothly and controllably as possible, utilizing the invisible hand of gravity to transfer the wine from one stage of vinification to another. It was a prescient move and many Bordeaux estates have gone back to simplified modus operandi.

The barrel cellar pictured from the upper walkway at Cos d’Estournel

The incoming fruit undergoes a strict selection, the Merlot given a cold-soak before fermentation, which is started using natural yeasts. “The first vintage to be vinified in the winery was the 2008,” Arangoits tells me as we inspect the vats from a walkway above. “The previous three vintages were made in a temporary facility in another building. Before that, we did not have much space and barrels had to be stored five tiers high. (This I vividly remember from my first visits...it was cramped to say the least.) We had to excavate 17 meters into the ground to enable the use of gravity transfer. We have 72 troconic, double-lined stainless steel vats: forty-eight vats 115 hectoliters in size plus another twenty-four vats that range between 20 and 60 hectoliters. There is a layer of insulation inside so that the temperature regulates similarly to cement.”

I ask how easily it is to estimate which lots will be vinified in which vats since yields vary from year to year. “Well, that’s a good question. We know about 80% what will happen before the harvest. That can be measured. Then 20% just depends on the circumstances. We usually isolate parcels where we are unsure about quality. I actually like the larger vats. I like the synergy between different parcels blended together. We usually do a four-week skin maceration depending on the vintage. We work more with délestage than remontage (bleeding the tank rather than pumping over). We do this manually without pumps. This is good for troconic vats because it allows the cap to breathe and it allows the berries to remain intact without compressing. What juice there is, stays in the berry. For the pressed wine, we use a vertical press and transfer it into barrel that we grade on four levels. We use about 8 to 10% vin de presse but these days we can obtain that by extracting less and being more gentle.”

As you can see from the tasting notes, the level of new oak has varied in recent years, sometimes the grand vin was raised entirely in new wood, such as the 1982 and 1986, whilst during the 1990s it was lowered to between 60% and 80%.

“We use ten different coopers using two or three different levels of toasting. There is no single dominant cooper that we use and that has always been our policy. We like the variety. It is important that the barrels keep the energy of the wines. From 2002 onwards we have done less racking because we have found that we do not need to give the wine too much oxygen.” The duration of barrel maturation is usually around 18 months, the first racking done the July following the harvest. Since 1994 there is a second wine, Les Pagodes de Cos, which comes from specific parcels rather than a winery selection. There is now also a Sauvignon Blanc dominated white wine, Cos d’Estournel Blanc, and the Merlot-driven Goulées by Cos d’Estournel from vineyards in the northern Médoc.

The Wines

These tasting notes derive from the vertical conducted by the château, augmented by more recent vintages from a separate tasting in London and bottles of my own. I have conducted verticals of nearly every Grand Cru Classé over the last twenty years and this retrospective of Cos d’Estournel was one of the most revealing that I have undertaken, highlighting periods of brilliance and spells where for one reason or another, quality deviates away from what I feel is the true character of the wine. I narrate vintages in chronological order.

A line-up of Cos d’Estournel, perhaps a sight I never expected to see given the dearth of bottles at the estate

Let me make a bold statement. Between the 1920s and the 1960s, Cos d’Estournel produced a constellation of astonishing wines that validate Louis Gaspard’s original, perhaps hubristic vision of his Saint-Estèphe estate competing with Lafite. I am not making that statement facetiously because of the reputation of the vintages in question, bottle age or the privilege of tasting them. It is an objective view comparing this era’s oeuvre with its peers. In some ways, the wines of this period mirror the consistency of Montrose and affirm how Cos d’Estournel needs time to reach its peak, rewarding those with the wherewithal and patience to cellar the wines for 20, 30 or 40 years or more. With respect to this vertical my palate is the beneficiary of the alchemical influence of time.

Cos d’Estournel 1928 and 1929

We commence with the 1928 Cos d’Estournel, a fêted vintage that produced masculine wines of unprecedented longevity. Both this and the 1929 Cos d’Estournel would have been overseen by Fernand Ginestet at the beginning of his tenure and they are both in remarkably good shape. Perhaps echoing the performance of the 1928 and 1929 Latour, it is the latter that really stands out, a sublime expression of perhaps the greatest inter-war vintage. The 1928 Cos d’Estournel is structured, solid and swarthy, yet the 1929 Cos d’Estournel is finessed, complex, chiseled to the finest degree, a more feminine wine that sparkles after almost a century. Both rank amongst the best that I have tasted from any Bordeaux property in those years. Even the 1933 Cos d’Estournel is drinkable, a surprise given this was a wretched growing season plagued by rain. Given that it predates appellation rules, I wonder if it might have been propped up by some of the superior 1934? It is not quite as good as the 1933 Montrose and it surely benefits from perfect provenance, but it deserves light applause just for hanging in there.

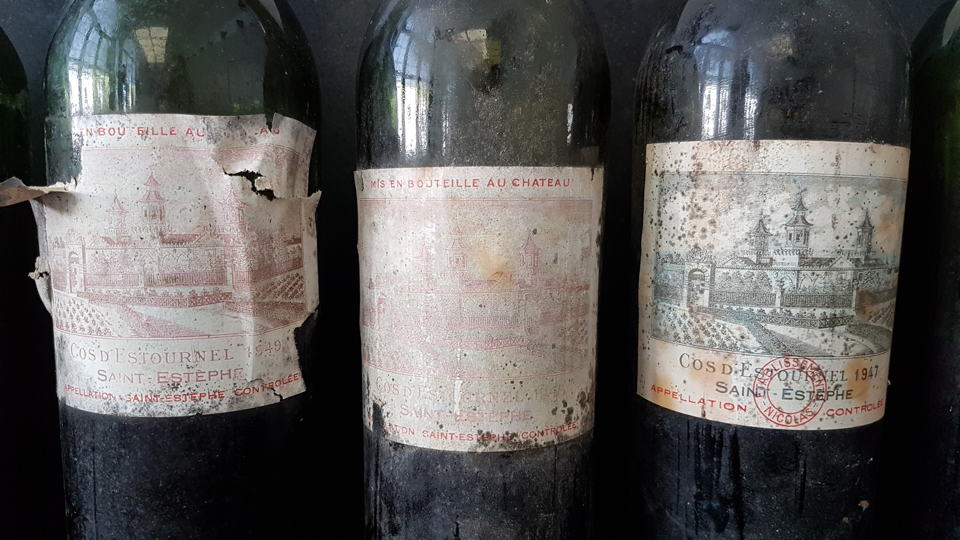

A triple whammy of postwar Cos d’Estournel: 1947, 1948 and the ethereal 1949

The 1945 Cos d’Estournel is an important wine personally, the first I ever tasted from this victorious year, bought from a merchant in days when such wines were far less expensive. Not only does it confirm the quality of Cos d’Estournel in this period, but it upheld the reputation of the 1945 vintage that up until then, I have only experienced vicariously. The bottle of 1947 Cos d’Estournel, like many in this vintage, is too volatile for my own liking. During that hot late summer, châteaux had no means to control fermentation temperatures other than dunking blocks of ice into the vat. I note that Antonio has a more positive encounter with another bottle in this Cellar Favorite. “No great wines, just great bottles” as the saying goes. The 1948 Cos d’Estournel comes from a rather forgotten vintage that is more reputed on the Right Bank. It is a solid, masculine wine that feels a little curmudgeonly in its old age, like a grumpy grandpa, although one must credit there being more fruit than I presupposed. Maybe it feels overshadowed by the 1949 Cos d’Estournel? It is an astonishing wine, without question the greatest old bottle of Cos d’Estournel that I have tasted. The only Left Bank 1949 that surpasses it in my experience is the spellbinding Mouton-Rothschild, but I seriously considered a rare three-digit score. It flirts with perfection, a kaleidoscopic bouquet of ineffable complexity, filigree tannin, beguiling symmetry and astounding length. Bottles are now rarely ever seen but if you ever encounter one for sale and provenance is sound, do not hesitate.

The 1955 Cos d’Estournel does not come from the vertical but courtesy of a gentleman in Beaune who opened and poured it blind over dinner. A second example was sourced from the same case that I tasted a couple of years ago and it is a marvel, yet another testament to the greatness of this growing season: fresh, beautifully structured and quintessential. The 1959 Cos d’Estournel is a vintage that I have only met once before out of double magnum. Coming so soon after the devastating spring frosts of 1956, I wonder if any fruit from young vines entered the blend? I don’t believe so, since parcels were replanted in the early sixties. It is a lovely wine with an opulent mint and fig-tinged bouquet, quite fleshy in texture and opulent, although I prefer the mighty 1961 Cos d’Estournel. This is your archetypal old school Claret that must have gone down a storm within pinstriped English gentleman’s clubs back in the day. It has a heavenly bouquet and perfect balance on the palate, perhaps not quite as persistent as the very greatest 1961s that I have tasted and yet certainly surfeit with class and sophistication. Perfectly stored bottles will continue to drink well. The 1964 Cos d’Estournel, like the 1955 opened by my Burgundy friend, evinces my view that whilst the growing season favors the Right Bank, the exception is the northern reaches of the Médoc. Both Montrose and Cos d’Estournel produced extremely fine wines in this year, unlike the rather diluted wines further south on the Left Bank. Whilst not quite reaching the heady heights as the 1955 or 1961, it remains a commendable wine.

Now let us move on to the 1970s. This was not a golden era for Bordeaux, beset by a run of difficult vintages, inveigled by salesmen offering quick-remedy fertilizers and herbicides to increase quality, a priori, high yields. Some Bordeaux château seem to defy all that and produced good wines. (Readers might remember my bon mots towards a 1972 de Pez recently.) However, Bruno Prats seemed unable to overcome the vintages and the wines perform poorly. The 1971 Cos d’Estournel is rustic and ferrous, though admittedly better than others I have tasted from that vintage. I am afraid the 1975 Cos d’Estournel is woeful, what feels like a ham-fisted, heavily chaptalized wine that must be considered a failure. The 1976 Cos d’Estournel is not much better, overwhelmed by that infamous dry hot summer, one-dimensional and enervated.

So we move on to the 1980s. The 1981 Cos d’Estournel is a vintage that I have encountered a couple of times before but not for some years. This performance suggests that this is beginning to reach the end of its drinking plateau, a little weak and fragile, redeemed by a lightly spiced finish. Drink soon if you still own any bottles, though larger formats might be interesting. The 1982 Cos d’Estournel is the vintage that put the estate back on the map. I have encountered this wine many times over the years, including one occasion lunching next to Russian oligarch/Chelsea football club owner, Roman Abramovic, who incidentally was cracking open a 1961 Palmer. I also remember a Cos d’Estournel themed dinner at the Tate Modern some years ago, Jean-Guillaume Prats joking that yields would have been extraordinarily high, perhaps as much as 100hl/ha given the abundance of fruit that year. The exact yield is a moot point. The 1982 is such as lavish, enjoyable wine that you cannot help but be seduced by its gamey notes, its warmth and generosity. Maybe it has just lost a little of its lustre in recent years, but I suspect large formats will be extremely pleasurable. The 1985 Cos d’Estournel is simply another in a long list of 1985s that are drinking beautifully at the moment, a wine with open arms that gives you a long hug. Don’t expect that from the 1986 Cos d’Estournel. It is masculine and structured, quite dense and still grippy after 32 years, yet it was a vintage that bestowed enough fruit to soak up the 100% new oak used at the time.

The 1989 Cos d’Estournel put in a perplexing performance. I have encountered decent bottles in the past but this one seemed to suggest that it has lost a lot of vigor and become frayed at the seams, unlike the splendid 1990 Cos d’Estournel. This is a beauty and might be stealing the thunder from the 1982: lavish and broad-shouldered, sumptuous and decadent whilst retaining the essence of the wine. I am grateful that the château opened the 1991 Cos d’Estournel. Of course, late spring frosts caused widespread damage to much of the Left Bank except for those whose microclimate is regulated by the turbid waters of the Gironde. Such is the case at Cos d’Estournel and the 1991 put in a creditable performance. Just before filing this article I chanced upon a half-bottle of 1992 Cos d’Estournel in a shop in Bordeaux, still wrapped in paper lying in its original case. Initially it was far better than my rather scathing note scribbled many years ago. Perhaps I had been wrong? Yet despite the aromatics being commendable, there is no denying that the finish is hard and one-dimensional. Conclusion – the 1991 is better.

As we move to the mid-1990s I feel that another era opens, one where the estate began to reshape itself, perhaps occasionally chasing critics’ numerical approval and forgot what made it special in the first place. I was told that they intentionally picked late in 1995 and that does not translate particularly well in the resulting wine. Vis-à-vis other vintages, it brought to mind a person wearing an ill-fitting suit. It felt rather cumbersome. Better is the 1996 Cos d’Estournel, mainly because the new oak was reeled in from 100% the previous year to a more modest 65%. Like the 1986, it is quite structured but shows better breeding and class. The 2000 Cos d’Estournel is big, bold and assertive, “darker” rather than “lighter” similar to many in that vintage and clearly requiring considerable cellaring. The 2001 Cos d’Estournel has a sense of symmetry that might be absent in its millennial counterpart and yet, my feeling is that it could have been a better wine, given that this is a reputed Left Bank growing season. Maybe it is moving into its secondary phase a little quicker than I would have expected?

The 2003 Cos d’Estournel is stupendous, affirming that quality bunches up towards Pauillac and Saint-Estèphe. In my opinion it does not quite have the same élan as the 2003 Montrose, yet it handles its lushness with aplomb and avoids any blowsiness. There is no disguising that it is cut from a totally different cloth to the classic wines of the 1950s and 1960s, yet it remains one of the handful of genuine successes of the 2003 vintage. The 2005 Cos d’Estournel, tasted as part of a horizontal organized by Goedhuis in April, confirms several previous showings and typical of the vintage: sultry yet compelling on the nose, almost saturnine on the palate as it slams the door in your face and says: “Don’t come back for another decade”. The 2006 Cos d’Estournel is a decent if not spectacular wine, although it is the one vintage where Montrose tripped over its shoelaces and Jean-Guillaume Prats certainly oversaw the better Saint-Estèphe, even if it lacks the pedigree of other vintages. The 2007 Cos d’Estournel comes from a rather maligned vintage, though I enjoy those secondary notes of Italian delicatessen that must surely emanate from the Merlot, one of the few forward wines that is ready to drink now.

That brings us to the most controversial wine, the 2009 Cos d’Estournel. I am on record as disliking this wine since I first tasted it from barrel, a wine that in my eyes felt predesigned to win critics’ approval but lacks the complexity, freshness and breeding that makes this Second Growth special. It felt excessively manipulated, an obvious wine and I am not alone in that opinion since perusing the database I note both Stephen Tanzer and Ian d’Agata hold similar views. As this wine has matured in bottle, I have softened my stance as it shed that boatload of puppy fat. Yet it retains that thick gloss that makes it rather vulgar compared to the 2008 and 2010, vintages I prefer. Each to their own. I remember telling Jean-Guillaume as such when I first tasted the brilliant 2010 Cos d’Estournel from barrel. “This is more my style of Cos,” I remarked to him directly during en primeur and it remains a fantastic expression of the vintage. Unlike the 2009, it retains the DNA of Cos d’Estournel. It is still a brute that requires fifteen, perhaps twenty years of bottle age to soften those Leviathan tannins, but it will be worth the wait. The 2012 Cos d’Estournel, which was tasted blind against its peers, shines with a conspicuous mineral-driven nose, embracing the opulence synonymous but crucially backing it up with complexity.

I finish with the re-tasted 2015 Cos d’Estournel, of course, made during Aymeric de Gironde’s tenure. I want to include it in this vertical because it illustrates the new chapter of Cos d’Estournel, returning to a more classic style, showing more finesse and restraint that lies in contrast to some of the more hubristic wines of the previous decade. Suffice to say that the most recent vintages have been some of the most satisfying to date and I cannot wait to revisit the 2016 that should have recently been bottled.

Michel Reybier and Dominique Arangoits posing next to the bottles following the tasting at the property

Final Thoughts

The vertical at Cos d’Estournel completely vindicates Louis Gaspard’s moment of inspiration as he stood in Lafite and envisioned a wine that could compete on the same level. That is not to say that there are periods when Cos d’Estournel lost its way, particularly in the 1970s, no doubt because of the poor growing seasons, perhaps also the late 1990s and 2000s. Not that I dislike that era’s wines. I just find the post-2010 vintages more characterful, brighter and fresher, recapture the charm and personality of Cos d’Estournel. The wines from the postwar period, perhaps back to the 1920s, attest the lofty heights that Cos d’Estournel can achieve. As I said before, these are wines that always demanded lengthy cellaring and it is a pity that so few exist, possibly consumed before their prime. In particular the 1929 and 1949 ranks amongst the elite wines of the 20th century. These bona fide legends are now extremely difficult to find but that is not the case for available recent vintages. Through improvements in the winery and in particular tannin management and more prudent use of new oak, Cos d’Estournel is more approachable, though I maintain that it deserves 15 years in bottle before it really shows what it is made of. Next time I visit Cos d’Estournel I will go up to the statue of Louis-Gaspard and thank him for his foresight in creating this maverick château that stands like a beacon on the Pauillac–Saint-Estèphe border.

(My thanks to Michel Reybier and Dominique Arangoits for organizing and attending this vertical tasting at the château.)

See the Wines from Oldest to Youngest

You Might Also Enjoy

Sharing Alike: Petrus 1947 - 2015, Neal Martin, September 2018

Aiming High: Haut-Condissas 1997–2015, Neal Martin, August 2018

The Marital Margaux: d’Issan 1945-2015, Neal Martin, July 2018

Cellar Journal – Bordeaux to Start…, Neal Martin, July 2018

Looking Back To Go Forward: Lafite-Rothschild 1868 – 2015, Neal Martin, July 2018