Browse using the new Vinous website now. Launch →

Printed by, and for the sole use of . All rights reserved © 2015 Vinous Media

Hurdling Over Time: 19th-Century Madeira

BY NEAL MARTIN | FEBRUARY 27, 2019

“I think Madeira and Burgundy carry combined intensity and complexity of vinous delights further than any other wines. There is possibly something unlawful about their rapture.” – Prof. George Saintsbury, Notes on a Cellarbook (1920)

The Epiphany

A glass of 1920 Blandy’s Bual shredded my prejudices and opened my senses to the kaleidoscopic delights of Madeira. I had foolishly presumed it was a fortified for fogeys – you know, the kind of beverage that rendered Grandma tipsy between the Christmas turkey and the Queen’s speech. Madeira was antiquated, retro, but not in a hip, post-modern way; it was the tipple of squares and weirdos. In 2003 I even booked a holiday to the island – an ironic gesture that thankfully backfired in life-changing fashion. Yes, I did find a sizeable percentage of the population white-haired and wrinkly. The island was not exactly party central; no Ibizan all-nighters on the beach (not that there are any beaches). But Madeira’s dramatic volcanic terrain took me by surprise: craggy mountains and deep ravines of pure basalt, not to mention the breathtaking drive along the north coast with the Atlantic roiling below that prompted me to once write: “The road chiselled into the cliff-face from São Vicente to Porto Moniz makes the A13 from Benfleet to Basildon seem dull by comparison.”

The spectacular coastline of Madeira, with a vineyard perched on top of cliffs overlooking the Atlantic.

Landscape aside, that unassuming glass of 83-year-old Bual, ordered out of curiosity at Blandy’s Lodge in Funchal, was the biggest revelation. My senses lit up. I looked at my watch. It was epiphany o’clock. And once you experience the glory of Madeira, it never leaves you. You join a secret society of Madeira fanatics, an underground resistance force that pledges to keep Madeira alive. It’s like Fight Club, though instead of shirtless men gathering in dark cellars to beat each other to a pulp, they gather in dark cellars to fight over Malmsey against Bual, the only angry words thrown being something like, You complete Bastardo. Unlike Fight Club, I am able to talk about it and indeed, write about it. Over the years I have penned a dozen articles on the subject, visited the island on a further three or four occasions and authored comprehensive reports. Numerous encounters with ancient Madeira have had a profound effect on my appreciation and sent me down the gyre of time to its year of birth, which could lie one or even two centuries in the past.

A Cellar Favourite notwithstanding, I open my Madeira account in audacious fashion and make no apologies for that. My original intention was to focus upon recent releases; unfortunately, other articles and deadlines waylaid me. But last June I did spare a morning for a friend and Madeira maven with a jaw-dropping collection, who invited me to a private tasting of 19th-century Terrantez. This grape variety arguably represents the apotheosis of Madeira. Alas, extant bottles from its halcyon days are rare as hen’s teeth, to the extent that one or two bottles in this report have never been documented and may never be encountered again. In the end, I decided to write two separate articles. This first piece focuses upon ancient Madeira, with the spotlight on Terrantez; a second one planned for later this year will examine new releases, hopefully in conjunction with a long-overdue visit to Madeira itself, not least because it would coincide with the 600th anniversary of the island’s settlement.

Madeira icons: bottles of Terrantez lined up at Noizé restaurant in London.

History

Before continuing, perhaps I should offer a potted history, since it provides context to this article. In the second part, I will describe the styles of Madeira that, in order of sweetness, comprise Sercial, Verdelho, Bual and Malmsey and the common workhorse variety, Tinta Negra Mole.

In 1419, three Portuguese sailors by the names of João Gonçalves Zarco, Tristão Vaz Teixeira and Bartolomeu Perestrelo were crossing the Atlantic Ocean when they chanced upon a craggy volcanic island that had thrust from the ocean 14 million years earlier. The first European settlers introduced viticulture and constructed levadas, irrigation channels that rendered the land agriculturally fertile, mainly for sugar cane. Wine was for intoxicating purposes only; however, Madeira’s serendipitous location slap-bang in the middle of busy shipping routes led to trade with British colonies, no less than Captain Cook docking the Endeavour to pick up 3,032 gallons of wine en route to the Pacific, for scurvy prevention as well as libation. In the 1700s, these white wines, often fortified with brandy, were found to have oxidised whilst stored down in the vessels’ hot and humid wooden hulls. In a second case of serendipity, this journey was found to improve instead of ruin the taste of the wines. These so-called vinho da roda, which had voyaged across the world and back via the tropics, became coveted, though it was not a radical invention, since the Romans had used similar techniques in heating amphorae.

Demand for Madeira came from Britain and its colonies, particularly the East and West Indies. By 1780 there were as many as 70 British Madeira houses on the island. Madeira gained immense popularity along the Eastern seaboard of the United States, particularly in cities such as Baltimore, Boston and Charleston, where wealthy families would build collections and hold Madeira parties. (Some readers may remember last year’s headline when a large cache of bottles and demijohns was discovered at the Liberty Hall Museum in Union, NJ, and subsequently auctioned for a pretty penny.) Pale Madeira designed for the American market was called Rainwater, a category that has been resurrected in recent years. Bottles destined for the US were often stencilled not with the shipper’s name, but the name of the vessel that transported the wine, or the recipients. As Madeira’s popularity slowly began to wane in Britain, the United States remained loyal, though troubles were brewing on the horizon.

Oïdium began its pernicious march across the island in 1851, and within a year 80% of vines had perished, along with many British shippers. The American Civil War stymied demand 10 years later, and from 1872, phylloxera kicked away the crutch of a once-flourishing industry. By the end of the 19th century, Madeira was gaining a reputation as the tipple of elderly gentleman, a démodé that Madeira has never quite been able to shake off. Noble grape varieties such as Bual and Sercial were usurped by the workmanlike Tinta Negra Mole or, worse still, ungrafted American vines known as direct producers. Other vineyards were abandoned or lost to urban sprawl. The industry dangled by a thread, held up by surviving British merchants shipping a handful of pipes each year, utilising stocks of mature Madeira blended to meliorate wines. That supply would not last forever.

In 1913, the Madeira Wine Association was created. Its primary aim was to amalgamate remaining shippers over a period of time, allowing them to retain independence and share resources. In reality, it was their only means of survival, since demand continued to decline after World War I, compounded by Prohibition in the US between 1920 and 1934. The nadir came when Madeira became better known as a cooking ingredient than as a beverage. Lodges grew dilapidated through lack of investment and the future looked bleak. Not until the 1970s did quality begin to improve, helped by the creation of the Instituto do Vinho da Madeira (IVM) in 1980. The IVM provided guidelines to supervise the industry and encourage farmers to cultivate noble grape varieties. Portugal’s membership of the European Union in 1986 imposed much-needed regulations, though it was another 15 years before the export of bulk Madeira for cooking purposes ceased. The Instituto do Vinho, do Bordado e do Artesanto da Madeira (IVBAM) currently lists just eight registered exporters of Madeira: Vinhos Barbeito, H M Borges, Henriques & Henriques, Justino, Pereira d’Oliveira and the Madeira Wine Company, which is branded mainly under Blandy’s, but also Cossart Gordon and Leacock’s. Two others produce Madeira only for visitors to the island.

In 2019, Madeira is on a steady footing and there is growing appreciation amongst wine writers and sommeliers that is slowly spreading to consumers. I would not claim Madeira has undergone a resurrection like sherry or gin. It is not a cool fortified to be seen drinking in bars. But there is a new generation of talented winemakers and estate directors, the likes of Ricardo Freitas at Barbeito and Chris Blandy, steering Madeira in the right direction.

What Makes Madeira “Immortal”?

Contrary to what I sometimes read, Madeira does not live forever, as romantic as the idea of immortality might be. Noel Cossart astutely observed that in his day and even more so in ours, we taste the minority of ancient bottles that survived, not the forgotten or faulty that fell apart after a short period of time. But compared to the human life span, yes, you could argue that Madeira does seem to last forever. Surviving bottles – the Madeira elite, so to speak – hurdle over decades with such ease that First Growths must gawp in disbelief. Madeira with just a few years on the clock can certainly be enjoyed. However, profundity begins to manifest when bottles attain half a century, and in my experience, the best reach an ethereal plateau around 100 to 150 years. That is no exaggeration. Some bottles of Madeira predating Queen Victoria have tasted more alive than some dubious primeur samples just a few weeks old.

Why is that?

Well, we must examine how Madeira is made. Since this article has a historical slant, I will not detail current techniques germane to recent vintages, though the basic principles have remained the same.

Up until the early 20th century, the fruit would be carried to the lodges in goatskin carriers (borrachieros) or barrels strapped to mules, sometimes wrapped in wet hessian to keep them cool and prevent any fermentation. Grapes would be pressed in rectangular wooden troughs, or lagares, under foot, often to the sound of traditional songs. Mechanical presses eventually replaced human feet, as they were quicker and more hygienic, though Noel Cossart found them “less conducive to a party.” “Wine is susceptible to atmosphere,” Cossart opined. “So why should it not start its long life with singing and dancing...” Exactly.

From the mid-1700s onwards, fermented wine would be fortified by cane sugar spirit or aguardente rather than the French or Spanish 96% rectified spirit mandatory these days (use of cane sugar spirit was banned in 1967). The fortified wine is known as vinho generoso and its alcohol is between 14° and 18°. The richer the Madeira, the earlier the fortification, so Malmsey might be fortified just a few hours after fermentation to preserve sweetness, whereas Sercial would be fermented dry. It had long been known that heat from the sun meliorated the wine, and initially storehouses were built with glass-panelled roofs to replicate the effect. In 1794, Pantaleão Fernandes introduced estufas, wherein the wine was heated by flues to around 70°C or even 80°C in a hot store or armazem de calor. Without any stipulation on temperature, unscrupulous shippers seeking shortcuts were tempted to excessively heat the wine so that Madeira could be produced rapidly and cheaply, potentially compromising quality. Concern was expressed by the likes of John Leacock and others, and indeed, estufas were forbidden for a short period of time. Thankfully, a decree issued in 1835 introduced temperature regulation: around 5°C per day up to a minimum of 40°C and a maximum of 50°C for a minimum of three months. Estufas are still used today for the finest Madeira, while ceramic or epoxy-lined concrete tanks are employed for larger, more commercial volumes. After cooling, the Madeira rests for 12 to 18 months, a period known as estágio, after which it is fined and racked, then transferred and matured in wooden casks or large tuns.

Madeira has a unique relationship with oxygen. This nemesis of ordinary wine plays a crucial role in the maturation of Madeira, an invisible scalpel that shapes its personality over years and decades. There is no negative connotation to the word “maderization” here. The chemical process is complex and not fully understood. Essentially, the ingress of oxygen through the pores of the wooden vessel is extremely slow (Liddell aptly describes the wood as a “filter”). The high levels of acidity and alcohol are gradually stabilized by oxygen and prevent the formation of acetic acid. Oxygen also reacts with proteins and amino acids to form an array of chemicals and aldehydes that lend Madeira its character. Eventually, Madeira becomes completely stable and unaffected by further exposure to oxygen, thereby guaranteeing that when you or I crack open a bottle, it will hardly have changed over weeks or months or maybe even years.

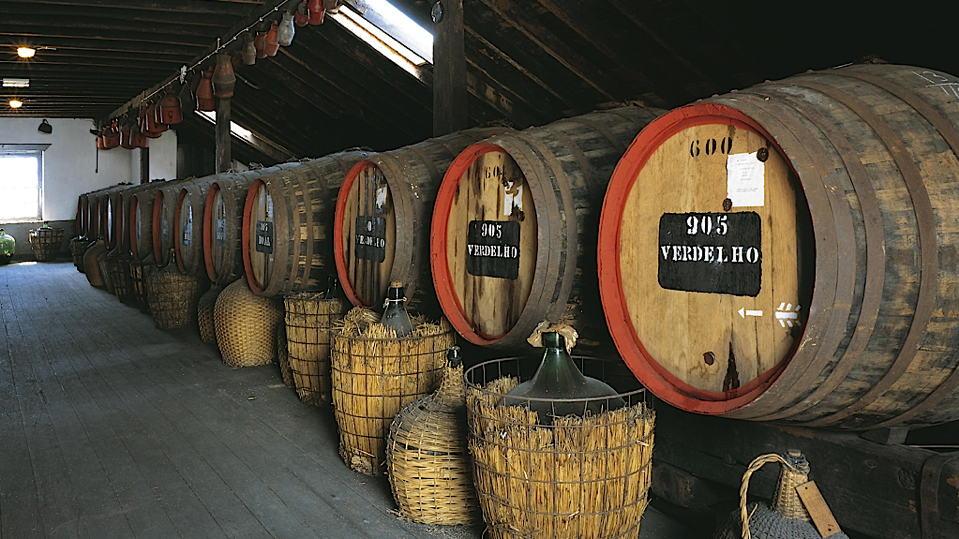

Blandy’s lodge in Funchal, where various lots of Madeira age in ancient wooden barrels and demijohns.

The buildings where Madeira is matured are known as adegas, the English referring to them as lodges, although traditionally they were called stores. Naturally, maturation over such a long stretch of time, a period known as canteiro, obliges topping up of the wooden vessel, a subject often not discussed since in strict legal terms, it is not allowed, not to mention that it fosters the notion of doctoring. As a ballpark figure, around 4% evaporates each year, although there are different factors at play. The type of wood and its porosity is obviously one element. Noël Cossart favoured American white oak, finding oak and chestnut too strong, whereas Henriques & Henriques preferred used whisky or sherry casks. The choice depends on the Madeira house. Other factors include the size of vessel, ambient temperature and humidity and so forth. Another option is to transfer the Madeira into 20-litre glass demijohns, often housed in wicker. Since glass is more inert and allows hardly any oxygen ingress, it dramatically slows down the oxidation and maturation, to the extent that Madeira can spend up to a century incarcerated in glass. This would be the course of action if the shipper felt the angels had had their share and desired no further ullage.

With respect to ancient Madeira, it is important to consider its journey. What is its source? How did it reach the present day? It is not like Claret, where you can pinpoint a château on a map and uncover the winemaker and maybe their practices at that time. The origins of ancient Madeira are often opaque and elliptical, details lost in the sands of time, a source of both fascination and frustration for aficionados. Collections were bought and sold between families, diverting their respective ageing onto different paths. The same cache might be partially bottled for a family member or an anniversary. Or perhaps they just felt that it was the right moment to bottle that demijohn gathering dust up in the attic over countless years. Fact is, some bottles are so old that records are long lost and anecdotal information irretrievable after the deaths of their collectors. Fortunately, there are informative books on the subject, and if this article piques your interest, then I recommend reading Madeira: The Island Vineyard by importer and aficionado Mannie Berk, and the essential Madeira: A Mid-Atlantic Wine by expert Alex Liddell, who was present at this tasting. In this article I have endeavoured to provide some context where available, either from the aforementioned books or from priceless information courtesy of Liddell or our host on the day. You will find this below or within the actual tasting note itself.

Though bottles from the 1700s still knock around, in my experience, the golden age is the latter half of the 1800s – or more accurately, from 1840 to around 1890 – which is why bottles from this period are now so sought-after and expensive. The most coveted Madeira can now fetch over $10,000 at auction. Not long ago these same bottles languished at the fag end of merchants’ lists, picked up for a pittance compared to now. Price escalation is the result of both rising demand and acutely finite supply, inevitably leading to a proliferation of fake bottles. Consider that most Madeiras are simply stencilled with shipper and vintage and you will understand that it is easier to reproduce than dry red wine. Provenance is crucial, more so today than ever before. During this tasting, we discussed suspect bottles, and our host slipped one dubious 1842 into the line-up in order to see how it differs.

Terrantez

I confess that I become starry-eyed over Terrantez, also known as Folgasão on the island. This does not imply that every Terrantez merits superlatives; however, a fair proportion of profound Madeira has consisted of this variety. It hits that sweet spot between richness, acidity and bitterness, sitting between Verdelho and Bual in style but with an uncommon citric note, almost like Japanese yuzu, and a dry, tangy aftertaste. The Romans described the sweet-bitter sensation as dolce-piccante.

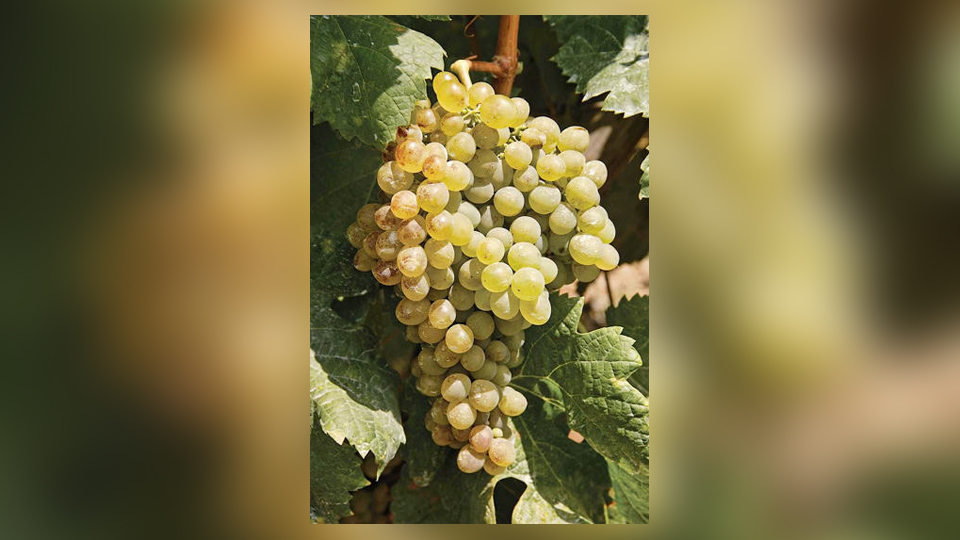

Thankfully, Terrantez was thrown a lifeline by both producers’ and consumers’ appreciation for the variety. This bunch belongs to Blandy’s.

One nugget of information gleaned during this tasting, courtesy of Liddell, is that although Terrantez was popular during the mid- to late 19th century, in the early days farmers had to be persuaded to plant the variety. Its yields were comparatively low and it was prone to rot, so they preferred to plant Sercial or Tinta Negra Mole. Terrantez rose to fame in the halcyon days of Madeira, and then its popularity waned to such a degree that by the 1920s it was on the cusp of extinction – where it has remained ever since. In his book, Liddell points out that just 1.52 hectares were planted to the variety out of a total of 476 hectares in 2012, though Chris Blandy told me that there are currently 22 registered growers of Terrantez totalling 4.08 hectares, so perhaps there has been an increase. “In a perfect year, the potential maximum production should hit 20,435kg,” Blandy informed me, “though this has never been hit.” Fortunately, that thread of survival has proven to be strong, partly because of the reverence afforded by Madeira aficionados and producers alike.

The Tasting

This tasting would not be possible without our host, Mr. D, who over the years has opened many spellbinding bottles of Madeira from his collection. The theme was Terrantez, though I have augmented these notes with others encountered in recent months in London, Hong Kong, Bordeaux and Beaune. For good measure, after digging through the clutter on my hard drive, I recovered a long-lost pre-auction tasting of Leacock’s Madeira, tutored by Michael Broadbent at Christie’s, though they did make the cardinal sin of not allowing the bottles to aerate enough, which I will explain further on. Perhaps they feared conflagration? Such was the heady fug of alcohol accumulating down in Christie’s tasting room that had somebody lit a cigarette, there would have been one almighty explosion. (Although the title does say “19th century,” readers should note that I have included just a small handful of 20th-century Madeiras that were included in this tasting or were recently tasted elsewhere.)

I have attended some memorable Madeira tastings in the past. The setting for this one was perhaps the most low-key, down in the basement of Noizé restaurant in Fitzrovia, at a long table with a dozen or so seats, whilst around us staff prepared for lunch. I will not detail all the bottles included in this article, and I restrict my prose to Terrantez, deviating “off-grape” when necessary. Let me name-check the stellar Madeiras, the ones that prompted choirs of angels and exultation. I often read eulogies for Madeira by dint of their age, and that should not be the case. The advantage of tasting many in one sitting is that they provide context. Readers should note that this is one occasion where I decline to give drinking windows, since they are inapplicable to bottles whose ageing bears no semblance to other wine. As a rule, Madeira is bottled because it is deemed ready to drink. There is no improvement by keeping it in bottle and thinking it will improve like dry red wine. Any amelioration comes from opening the bottle and ideally allowing three or four days for it to settle in contact with the air. This was done with the bottles at Noizé.

One producer that often appears at the top of my list is Lomelino. The first member of the Lomelino family to set foot on the island was Giovanni Baptista Lomelino in 1476. The company was formed in 1820 when the majestically titled Tarquinio Torquato de Câmara Lomelino bought shipper Robert Lear. His brother-in-law Carlo de Bianchi took over the business on his death and accumulated a prized stock of old Madeira that supplied royalty in Sweden, Italy and Portugal. Patrick Grubb mentioned that Lomelino entered Madeira wines into competitions and sold many bottles in Paris, and suggested that the company was the first to introduce genuine Madeira to France. The company, like so many, was eventually absorbed into the Madeira Wine Company in 1934. The 1841 Terrantez comes from a vintage that to all intents and purposes is written out of history, with no mention in Cossart’s adumbration of vintages, which skips from 1840 to 1842, and without a single documented sale at auction. Is this the only bottle in existence? It was sensational and encapsulated everything one could wish for in Madeira of this age and type. It electrified the senses in a way few others could hope to replicate. Likewise, a 1906 Malvasia, opened by our host at the end of a marathon La Paulée, was so rich and sumptuous and yet ineffably complex and delineated that I had to resist eloping into the streets of Beaune. Occasionally you find Madeira so vivid that there is some kind of synaesthesia. In this instance, this Malvasia shone blue.

Another favourite producer is Leacock’s. The firm was founded in the 1750s and run by William Leacock in the early 19th century. It was absorbed into the Madeira Wine Company in 1925 and Blandy’s still occasionally uses the brand name. Many of the notes in this article derive from the aforementioned pre-sale tasting at Christie’s, although others come from the Terrantez tasting at Noizé, not least the imperious 1846 Terrantez. This is a formidable Madeira, one that was crowned “Best in Show” when I participated in a similar epic tasting in New York. I have been fortunate to taste four Terrantez from this vintage, and Leacock’s seems to come up trumps thanks to its sublime, otherworldly bouquet and effortless balance on the palate. Only nine bottles have ever appeared for sale, in a single lot, and to taste this twice is a privilege. It conveys a sense of profundity and complexity that puts its a step ahead of the 1846 Terrantez from H M Borges and Avery’s, both magnificent in their own right. One challenger is the spellbinding 1846 Terrantez from MWC, which was bought from the famed Graham Lyons sale, the source of some of the most dazzling bottles I have consumed. (One might assume the acronym stands for Madeira Wine Company, but this long predates its formation.) It was transcendental on the nose of Seville orange marmalade and furniture polish, intense yet detailed and quite spicy on the palate, but shared the same effortlessness as the Leacock.

The 1817 Terrantez from Vanda Gonçalves Family was fascinating, not just because it is a very rarely seen vintage apropos of Madeira, but also because I had never tasted a bottle from the Gonçalves family. I assumed that she was an ancestor of the Gonçalves that founded Henriques & Henriques in 1850, although Francisco Albuquerque, head winemaker at Blandy’s, believes the bottles originate from the Vasconcellos family in Jardim do Mar. The bouquet augured little, coming across one-dimensional compared to the preceding 1846s, yet the palate was imbued with ample sweetness and freshness, remarkable for a wine over two centuries old.

If there is a single Madeira that exemplifies the ageing ability of Terrantez, it is Oscar Acciaioly’s 1802 Special Reserve Terrantez, lionised by Michael Broadbent in his Vintage Wine bible. This is not quite as rare as others mentioned in this piece, since a “whopping” 132 bottles of the 1802 were sold at Christie’s. The Acciaioly family were ducal descendants from Burgundy and migrated to the island in the 1500s, apparently bringing the Babosa grape with them. When Oscar died in 1979, his trove of wines was divided, half inherited by his second wife, who in turn sold them to Barbeito, and the other half inherited by his sons and subsequently sold through a series of sales at Christie’s. It was not the only Madeira wine auctioned in comparatively high volumes, and consequently prices were low, the gavel coming down on the 1802 for just $229 per bottle. You won’t find it for that price these days. This was my second encounter, and both testified to a remarkable Madeira wine with life-affirming intensity on the nose that follows through on a vivacious and quite assertive palate.

Final Thoughts

Madeira will always be of niche interest, yet such is its uniqueness and intrinsic quality that it deserves coverage, which is exactly what I intend at Vinous. Prices mean that I have to rely on altruistic friends to experience these bottles first-hand, since they are well beyond my own pockets. Truth is that we are reaching a stage where few ancient Madeira now appear for sale, and I am fortunate that my career coincided with a window of relative accessibility. In another decade? Who knows. This article is likely to be a one-off in the sense that I doubt it will be or can be repeated. To give you some idea, the accumulated bottle age within this report is more than 6,000 years. Despite their rarity, I believe in a duty to log and record their existence, to ascertain their intrinsic qualities as objectively as possible. In reality, my verbiage and scores can never translate the emotion of imbibing a wine from a different chapter of history, a wine that is no relic but a living wine cruising at its everlasting peak. Alas, rules forbid me from awarding ancient Madeira 100 points for merely existing. As I already mentioned, I will next take a look at more recent vintages that are available and represent good value. This has been a look into the past, but in many ways the present is even more interesting.

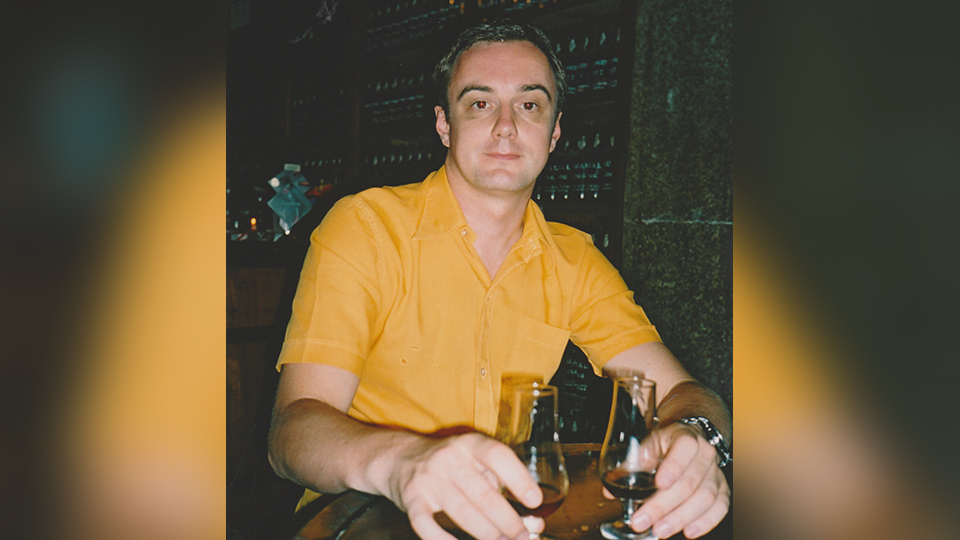

Lastly, that moment of epiphany... When researching this article, I flicked through photographs of my first trip to Madeira in 2003. There I found the picture below. Here is yours truly at Blandy’s Lodge at epiphany o’clock, and there, next to the obligatory slice of Madeira cake, is the revelatory 1920 Bual. Nothing was the same again.

My sincere thanks to Mr. D for organizing this tasting and providing such a unique array of bottles, not to mention opening so many incredible Madeiras over the years. Thanks also to Alex Liddell for his insights during the tasting.

You Might Also Enjoy

Port Is For Life: Symington Vintage & Tawny Ports, Neal Martin, December 2018

Vintage Port – The 2016 Declaration, Neal Martin, June 2018

Cellar Favorite: 1948 Taylor Fladgate Vintage Port, Neal Martin, June 2018

Cellar Favorite: Blandy’s Madeira – Recent Releases, Neal Martin, March 2018